On Toynbee

Arnold J. Toynbee: The Man Who Saw It All Coming

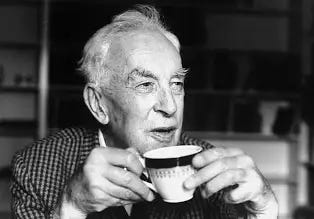

“Civilizations die from suicide, not by murder,” mused Arnold Toynbee—the tweedy, soft-spoken prophet of cultural apocalypse. He peered through the dusty annals of history and saw, with chilling clarity, the trajectory of human civilization. Self-inflicted death, he said, as if to add insult to injury.