On The Hollowing Middle

The Vanishing Common Life (Class Series, Essay 2)

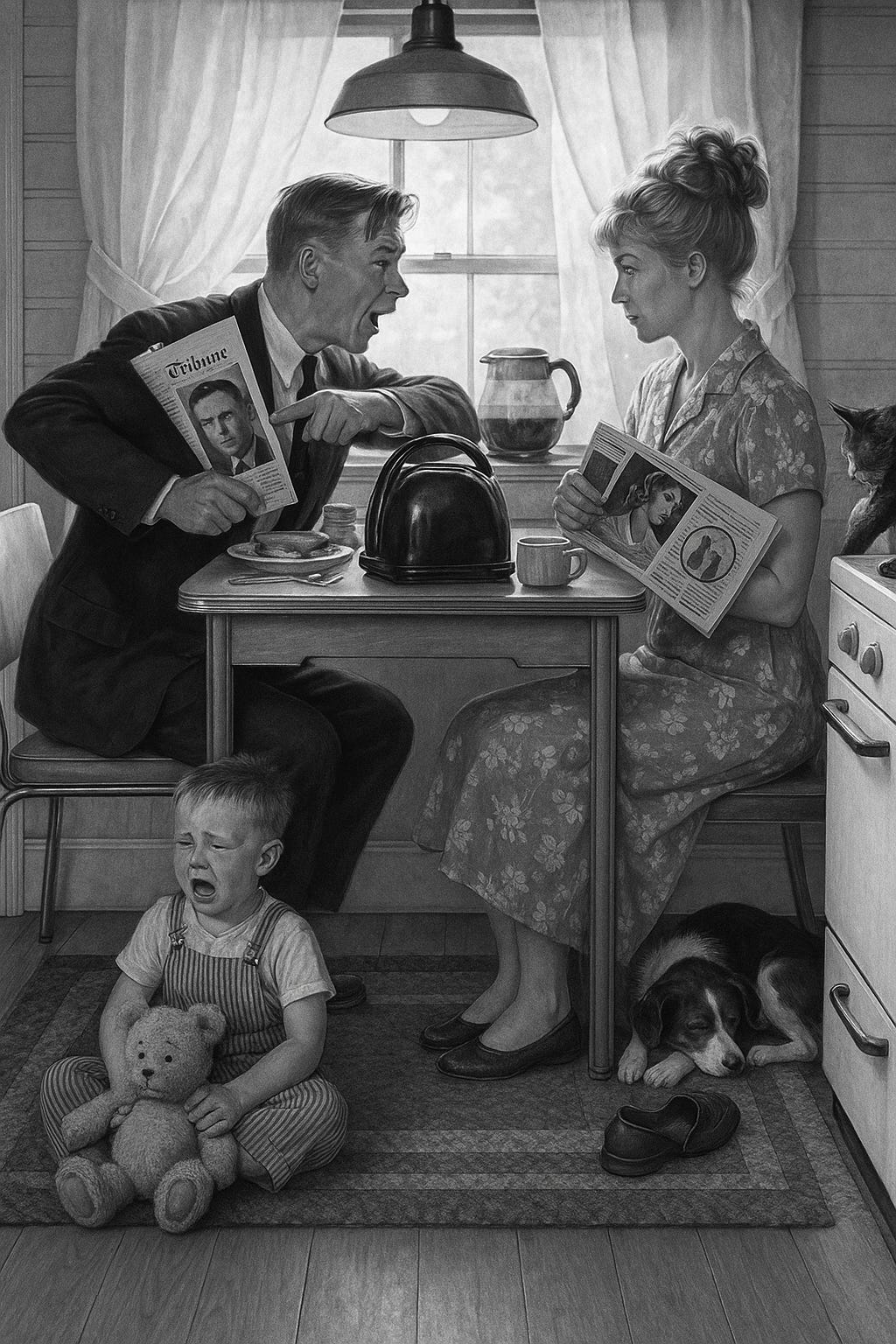

“The middle class was not just an income bracket; it was the American identity itself.”

For much of the twentieth century, America was its middle class. A factory worker in Cleveland, a teacher in Denver, and a salesman in Des Moines all claimed the same name. They drove the same cars, watched the same three networks, and leafed through the same Sears ca…