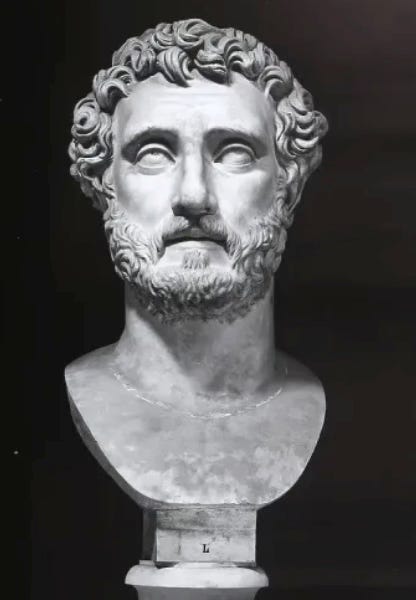

On The Emperor Who Didn’t Need to Write

Why Antoninus Pius Lived the Stoicism Marcus Aurelius Had to Record

“Concentrate every minute like a Roman-like a man-on doing what’s in front of you with precise and genuine seriousness, tenderly, willingly, with justice. And on freeing yourself from all other distractions. Yes, you can-if you do everything as if it were the last thing you were doing in your life, and stop being aimless, stop letting your emotions over…