On The Cup Runneth Over

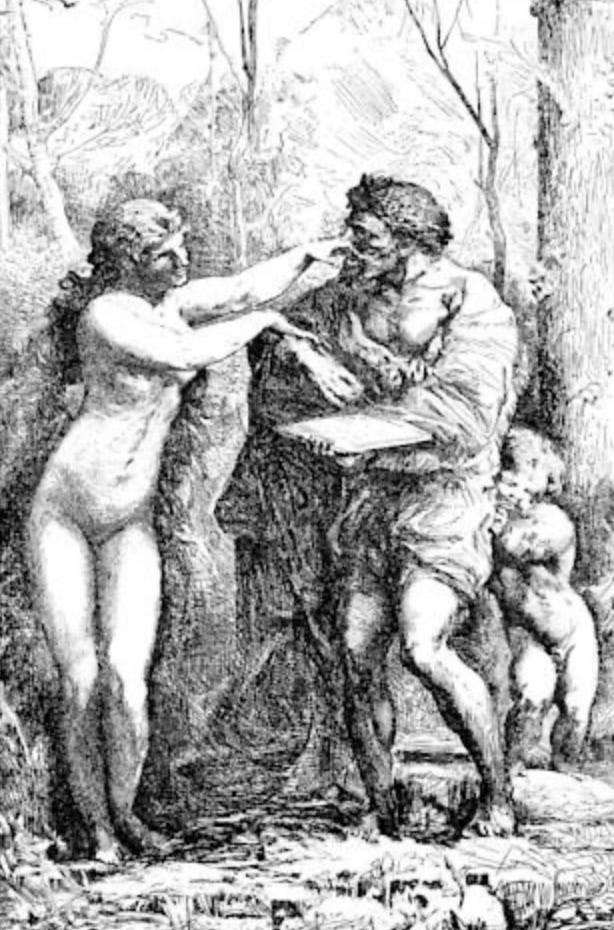

Part III of the Civilizational Drink Series - Alcohol, Sacrament, and the Metaphysics of Ecstasy

“Take, drink; this is my blood of the covenant…” - Jesus Christ, Gospel of Matthew 26:27–28

In nearly every era of civilization worth the name, alcohol played a foundational role. In short, man requires a substance for forgetting. For easing the pain of time. For fermenting memory into ritual. We misunderstand it only when we strip it of its context, whe…