On The AI Plateau

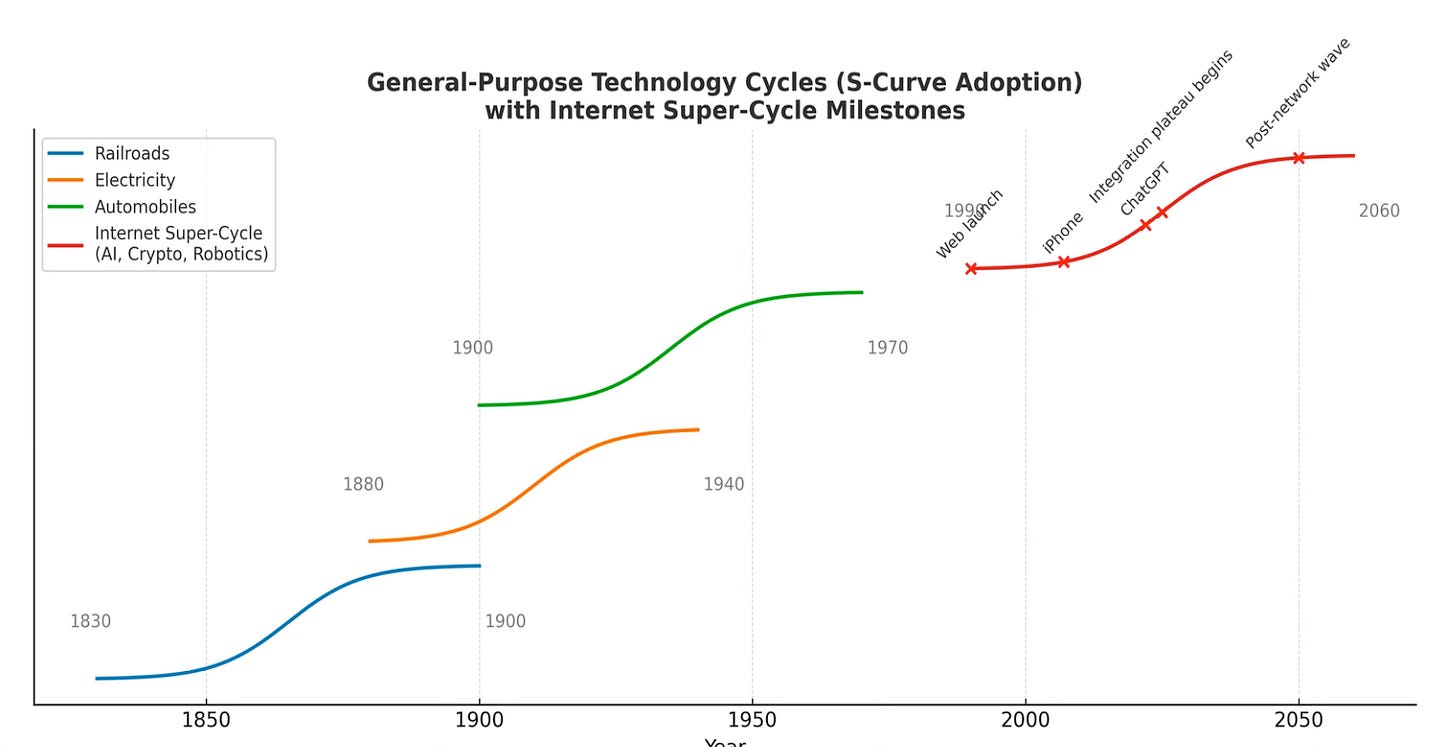

In Historical Perspective

The period of frenzy is followed by the period of deployment; the time to harvest the fruits of the revolution. - Carlota Perez

The AI hype cycle is over for now. I’ve been an AI advocate since the first time I used GPT-4 to write a working Python trading algorithm in 2023. I’m still convinced it will take the wider economy years, maybe decades to fully …