On Strategy

Propter rationem belli : For strategic reasons

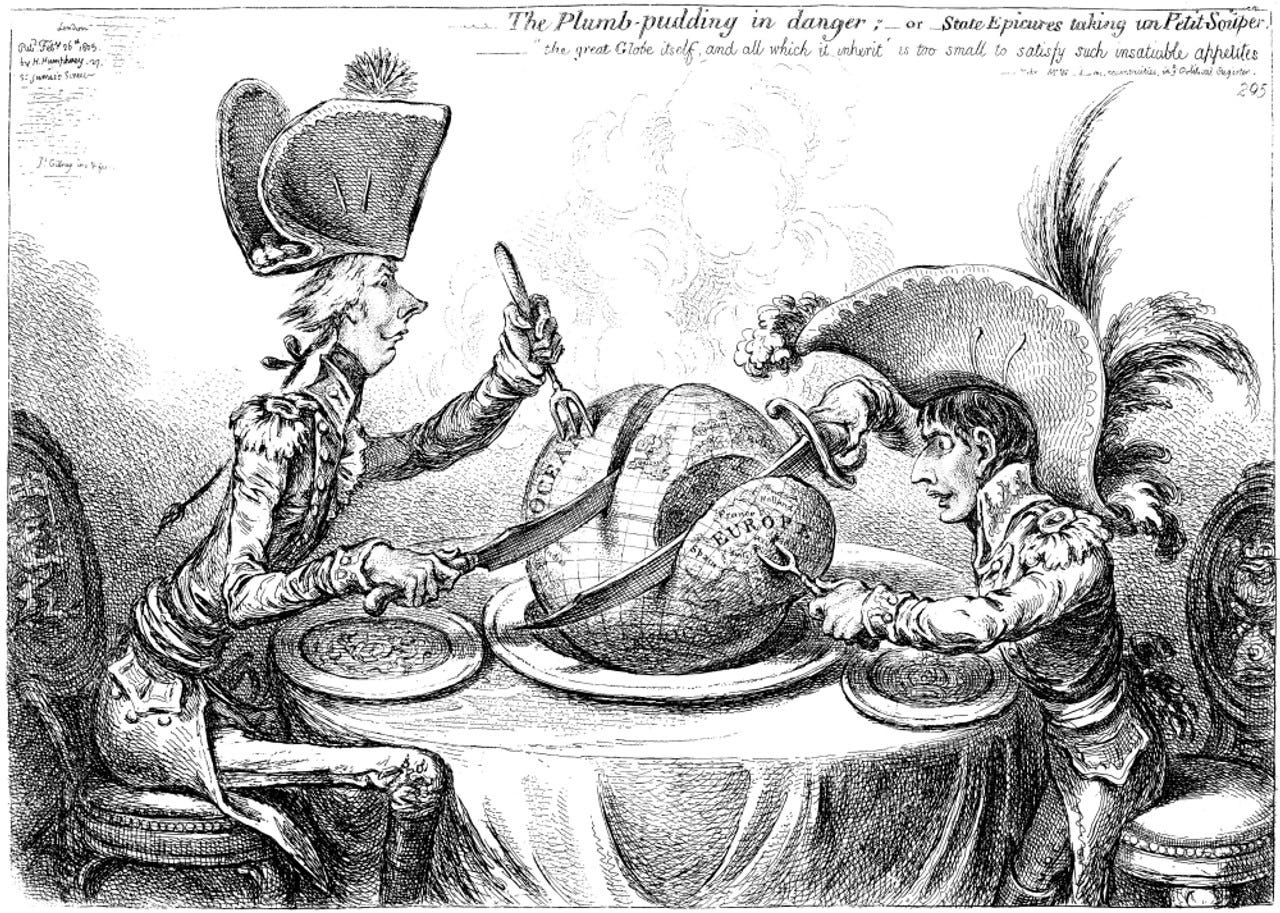

Nothing is more difficult, and therefore more precious, than to be able to decide. - Napoleon Bonaparte

Noble strategy can be summarized as the alignment of potentially infinite aspirations with necessarily limited capabilities. The same could be said for strategy of life. Once one is able to internalize this, one can thrive in any domain.

If one seeks e…