Money is probably the most successful story ever told. It has no objective value... but then you have these master storytellers: the big bankers, the finance ministers... and they come, and they tell a very convincing story. - Yuval Harari

In English, a bubble that doesn't pop is called "money." Money is always fundamentally overvalued. Its purchasing power is independent of its direct physical usefulness. This is obvious for paper money, but true even for bitcoin, gold and silver.

Path dependence

Money is path-dependent, it is a stable result of events that may be completely random. Money is an emergent phenomena that arises from complex adaptive systems like human societies. Money is something that has spontaneously arisen in almost every civilized society. It seems as if money is vital to thrive economically if a society exceeds a number even as low as the Dunbar number.

Using modern nomenclature, money evolves in four phases:

Collectible: In the first phase of its evolution, money will be demanded solely based on its unique properties. Shells, stones, beads and gold were all collectibles before later transitioning to their more familiar roles as money.

Store of value: Once money is demanded by enough people for its attributes, money will be recognized as a means of keeping and storing value over time. As a good becomes more widely recognized as a suitable store of value, its purchasing power will rise as more people demand it for this purpose. The purchasing power of a store of value will eventually plateau when it is widely held and the inflow of new people desiring it as a store of value wanes.

Medium of exchange: When money is fully established as a store of value, its purchasing power will stabilize. Having stabilized in purchasing power, the opportunity cost of using money to complete trades will diminish to a level where it is suitable for use as a medium of exchange.

Unit of account: When money is widely used as a medium of exchange, goods will be priced in it. I.e., the exchange ratio against money will be available for most goods. Think how many things are priced in the US dollar even outside of the United States. Only when merchants are willing to accept the new form of money for payment without regard to the exchange rate against the current money can one truly think of it as having become a unit of account.

Currently, the US dollar is being debased at levels not seen outside of war times. The US dollar is becoming less and less valuable, thus holding fiat currency is nearly worthless as the purchasing power continues to decline. We are approaching an inflection point where most people will willingly trade their fiat for bitcoins, equities, and precious metals.

Bitcoin, the newest of the contenders listed above is currently transitioning from the first phase of monetization to the second phase. By the end of 2021, bitcoin may even be widely used as a medium of exchange. It is striking to note that the same transition took centuries for gold, while Bitcoin is traversing the same terrain in just over a decade. No one alive has seen the real-time monetization of a good (as is taking place with Bitcoin), so there is little experience regarding the path and speed in which this monetization will take.

Money is a consequence of its own history. Not every asset can serve as money, but not every asset that can serve as money will be used as money. - Carl Menger 1892

The connection of current demand to past prices is known as path dependence and is perhaps the greatest source of confusion in understanding the price movements of monetary goods.

In the process of being monetized, a monetary good will soar in purchasing power. Many have commented that the increase in purchasing power of bitcoin creates the appearance of a “bubble”. While this term is often used disparagingly to suggest that bitcoin is grossly overvalued, it is unintentionally apt. A characteristic that is common to all monetary goods is that their purchasing power is higher than can be justified by their use-value alone.

Indeed, many historical monies had no use-value at all. The difference between the purchasing power of a monetary good and the exchange-value it could command for its inherent usefulness can be thought of as a monetary premium. As a monetary good transitions through the phases of monetization, the monetary premium will increase. The premium does not, however, move in a straight, predictable line.

Take for example, a good F that was in the process of being monetized may be outcompeted by another good G that is more suitable as money, and the monetary premium of F may drop or vanish entirely. For example the monetary premium of silver disappeared almost entirely in the late 19th century when governments across the world largely abandoned it as money in favor of gold. This is what seems to be happening with a flow from fiat currencies and gold to bitcoin and cryptocurrencies.

When the purchasing power of a monetary good increases with increasing adoption, market expectations of what constitutes “cheap” and “expensive” shift accordingly. Similarly, when the price of a monetary good falls, expectations can switch to a general belief that prior prices were “irrational” or overly inflated.

The truth is that the notions of “cheap” and “expensive” are essentially meaningless in reference to monetary goods. The price of a monetary good is not a reflection of its cash flow or how useful it is but, rather, is a measure of how widely adopted it has become for the various roles of money.

Money acts as the foundation for all trade and savings, so the adoption of a superior form of money has tremendous multiplicative benefits to wealth creation for all members of a society. Hard money, or rather, a money that is not constantly debased is an asset that people want to hold rather than spend as quickly as the acquire it.

We can call the transition from fundamental to monetary value "monetization." Menger and other early Austrian economists analyzed monetization in a primitive barter economy. They showed that money is a market phenomenon, that it can develop spontaneously without any official seal of approval.

An elucidation

Comparing two hypothetical cases:

In case 1, ten million people decide right now to move all their savings into Tesla stock, buying at the current market price no matter how high.

In case 2, ten million people decide right now to move all their savings into Bitcoin, buying at the current market price no matter how high.

In both cases each of these investors has an average of $1,000. So, $10 billion US dollars is active.

Neither Bitcoin nor Tesla can instantly absorb $10 billion without considerable short-term increases in price, this is called slippage and is something to be avoided if possible. Because it would require us to predict precisely how other investors would react, we have no way to precisely compute the effects. But, we can describe them in general terms. This is a Keynesian beauty contest in a nutshell.

In case 1, the conventional wisdom is right. The investors should expect to lose a lot of money.

This is because Tesla has a stable equilibrium price which is set by the market's estimate of the future earning power (price-to-earnings ratio) of this corporation. Because it is not the result of any new information about Tesla's business, the short-term surge should not affect this long-term equilibrium.

Since there will almost certainly be a short-term price spike, many of the investors will be buying at prices well above the stable equilibrium. In fact, the more investors added to the test, the more each one should expect to lose.

But there is no way to apply this analysis to case 2.

Bitcoin has no price-to-earnings ratio. With no formal link between bitcoin prices and currencies, there is no stable way to price it. There is no obvious equilibrium to which the bitcoin price must converge.

Thus, we can say that bitcoin, for example, is overvalued if bitcoin miners/holders are selling more bitcoin than speculators want to buy. Speculators will increase their bitcoin positions via leverage to trade in the markets to make a quick return and then cover their leverage. Speculators see opportunity in the volatility of bitcoins price, this allows them to trade in and out of positions quickly. Speculators are not long term holders or investors they are simply looking for assets to scalp profits from. Cash and carry is their bread and butter.

All of this assumes that there is no investment demand for bitcoin. On the basis of this assumption, it shows that bitcoin is a bad investment. Therefore there should be no demand for it. The popularity of this logic is astounding. However, it is a safe bet that most people who own bitcoin do not follow it.

Therefore, when our case 2 investors put $10 billion into bitcoin, that money has to be used to bid bitcoin away from its current owners, many of whom already believe that the price of bitcoin in dollars should be much higher than it is now. One can consult the stock to flow model and other such models to see the price appreciation many holders envision.

So, the result of case 2 is that the bitcoin price will, as in case 1, rise immediately. But, it has no reason to fall back. In fact, quite the opposite. Because the bitcoin price is largely determined by investment demand, any increase in price is evidence of increasing investment demand.

Mining production remains stable due to the difficulty adjustment present in the underlying Bitcoin code. Investment demand is a consequence of investors' opinion about the future price of bitcoin—which is, largely determined by investment demand.

This is not a circularity. It is a feedback loop. Austrian economists explain this phenomena by way of the regression theorem.

Certainly, the same mechanism can drive the bitcoin price down as well. When savings flow out of bitcoin, the price must drop. The reputation of bitcoin as a volatile investment is by no means undeserved. There is a trading range within which the price of bitcoin can fluctuate arbitrarily. The range is limited at the bottom by the cost to mine bitcoin when investment demand is zero.

It generally takes a significant external change to affect the long-term direction of a big feedback loop like the bitcoin market. Thus, it is rational for the market to actually treat the price spike caused by case 2 as a signal that the feedback loop is accelerating, and buy more. Studying memetic behavior and reflexivity by Rene Girard and George Soros shed light on the memetic accelerants in reflexive feedback loops and their works are worth a read in the current economic environment.

So, the case 2 investors are more likely than not to profit on their purchases. Obviously the purchases must happen in some sequence, and the earliest will do the best. But all have a good reason to participate, even the last, because their purchase will signal other investors who are not in the case 2 group to enter the market after them.

Nash equilibrium

The Nash equilibrium is one of the simplest concepts in game theory. In game theory parlance, a "game" is any activity in which players can win or lose—such as, of course, financial markets. A "strategy" is just the player's process for making decisions.

A strategy for any game is a "Nash equilibrium" if, when every player in the game follows the same strategy, no player can get better results by switching to a different strategy. This is a profound discovery as it allows one to model optimal strategies outside of direct cooperation with other participants.

If you think about it for a moment, it should be fairly obvious that any market will tend to stabilize at a Nash equilibrium. For example, pricing equities and bonds by their expected future return is a Nash equilibrium. No market is infallible, and it is possible that one can make money by intentionally mis-pricing securities. But this is only possible because other players make mistakes.

A Nash equilibrium analysis of financial markets is not a new idea. It is basic economics. The only reason you are reading about a Nash equilibrium analysis of the interaction between cryptocurrencies, precious metals, and fiat currencies now is because it is still a novel idea that few in mainstream academia and media fully grasp.

What Nash equilibrium analysis tells us is that the "case 2" approach is interesting, but inadequate. To look for Nash equilibria in the cryptocurrency markets, we need to look at strategies which everyone in the economy can follow.

Let's focus for a moment on the cryptocurrency at the forefront, Bitcoin. One obvious strategy, let's call it strategy B—is to treat only bitcoin as savings, and to value any other good either in terms of its direct personal value to you, or how much bitcoin it is worth.

For example, if you followed strategy B, you would not think of the dollar as worthless. You would think of it as worth 2,000 satoshi, because that's how much bitcoin you can trade one for.

What would happen if everyone in the world woke up tomorrow morning, grabbed a cup of tea, and decided to follow strategy B?

They would probably notice that at 2,000 satoshi per dollar, the broad US money supply M3, at about $19.3 trillion, is worth about 393,877 bitcoin; that all the bitcoin mined in history is about 18,600,000, with 2,000,000 or so lost and out of circulation. There is also an additional 1,000,000 bitcoin in the wallet of the founder Satoshi along with many other instances of bitcoins being locked up long term through trusts and lending platforms. All of this illuminates why the finite supply of 21,000,000 bitcoins is a metric that people use to value its underlying scarcity. The first time true digital scarcity has been created.

They would therefore conclude that, if everyone else is following strategy B, it will be difficult for everyone to obtain 0.13 of bitcoin in exchange for each dollar they own.

Fortunately, there is no need to follow the experiment further. Of course it's not realistic that everyone in the world would switch to strategy B on the same day.

The important question is just whether strategy B is stable. In other words, is it a realistic possibility that everyone in the world could price all their savings in bitcoin? Could all rights to dollars, euros, etc, just be converted to bitcoin and resolved? Or would there be some pressure to revert to paper fiat currency?

If Bitcoin bits were sized in absolute indivisible blocks, distribution would pose an obstacle. But measuring arbitrary small amounts of bitcoin in the form of Satoshis is not a difficult technical problem. The fact that bitcoins can be moved around the world in a nearly frictionless manner is yet another reason it is superior to gold.

It's true that there are serious inefficiencies in circulating actual coins made of precious metals. Spend too much time reading financial history and you'll be deluged with frightening facts about agio, gold points, clipped and worn coin, and so forth. Perhaps the worst problem is just that since metal coins have all these problems, there is a strong incentive to replace them with paper notes which are redeemable for actual metal on demand. Unfortunately, the note issuer then finds it very easy to print more notes than it holds metal.

These problems are all solved by the Internet. In a modern Bitcoin Standard there is no reason for money to consist of anything but secure electronic claims to precise satoshis of bitcoins. The Bitcoin itself should stay in independently audited forms of storage.

This mechanism is already being used, but is still in its infancy, because they are not well-connected to existing financial networks. Take for example how the advent of gold and silver ETFs, GLD and SLV are similar if more primitive. Converting them to support direct payment would be a small matter of programming. This is a precedent that bitcoin can build upon. A Bitcoin ETF seems inevitable at this point and will lead to another form of holding and connection to legacy financial networks.

19th-century Banking School doctrine, inherited by both Keynesians and monetarists, state that an expanding economy depends on an expandable currency.

Gilded Age financiers did succeed in embedding this principle in the institutional fabric of the West. But it has no rational explanation and is not proven in the wild. Of course the status quo need justify itself to no one, and it is possible that if monetary expansionism felt institutionally threatened it could present a more coherent narrative.

But to me the idea seems to rest on the understandable, but essentially numerological, connection between X% new money and X% growth, and on the indisputable fact that turning off the money spigot tends to result in a recession. Since today's economists (except of course the Austrian School) have abandoned the apparently unfashionable concept of causality in favor of the reassuringly positivist view of pure statistical correlation, it has escaped their attention that when one stops using a vice, one feels awful. Arbitrarily creating money in an economy is like someone smoking more and more cigarettes, the person needs to keep smoking more to get the same effects and in both cases it is nearly impossible to sustain.

It is also bruited about that without money creation to dissuade savers from hoarding cash, no one will lend or take any entrepreneurial risks. However, the Dutch, who ran a 100% hard-money economy for 150 years, were the most prosperous nation in Europe. Perhaps if Lord Keynes had actually underwent an entrepreneurial endeavor in his time, he would have rethought his views on lending, interest and risk. In general, stable periods of hard money have been among the most prosperous in human history. When the value of ones money grows with no risk or financial overhead, it may actually be a good thing.

So, absent of course any errors in the above polemic, strategy B is in fact a Nash equilibrium. A direct Bitcoin standard in which private citizens own bitcoin would be a viable foundation for a new global financial system. There are no market forces that would tend to destabilize it.

Further analysis

Let's step back for a moment and look at why people "invest" in Bitcoin in the first place. Obviously they expect its price to go up—in other words, they are speculating. But as we've seen, in the absence of investment the bitcoin price would be determined only by mining supply and demand, a fairly stable market. So why does the investment get started in the first place?

What's happening is that the word investment is obfuscating two separate motivations for buying bitcoin.

One is speculation, a word that has negative associations in English, but is really just the normal entrepreneurial process that stabilizes any market by pushing it toward equilibrium. An entrepreneur uses saved capital in a way to create more capital. It is risky, but the payoffs can be quite rewarding.

The other is saving. We can define saving as the intertemporal transfer of wealth. A person saves when they own valuable goods now, but wishes to enjoy their value later. This person has a high time preference.

The saver has to decide what good to hold for whatever time period they are saving across. Of course, the duration of saving may be, and generally is, unknown. Unexpected things happen which may cause a drawdown in the amount of savings. This is why liquidity in savings matters. It is harder to sell a house than it is a cryptocurrency.

And of course, every saver has no choice but to be a speculator. The saver always wants to maximize their ‘savings' value, as defined by the goods they actually intend to consume when they use the savings. For example, if our saver is an American retiree living in Panama, and intends to spend their savings on local products, their strategy will be to maximize the number of Panamanian balboas they can trade their savings for.

Here are five points to understand about saving.

One is that since people will always want to shift value across time, there will always be saving. The level of pure entrepreneurial speculation in the world can vary arbitrarily. But saving is a human absolute. Asymmetric reward for speculating is one of the ways in which savings are transferred from one person to another.

Two is that savers need not be concerned at all with the direct personal utility of a medium of saving. Our example saver has little use for bitcoin. Their plan is to exchange it for piano lessons and delicious tacos.

Three is that from the saver's perspective, there is no artificial line between "money" and "non-money." Anything they can buy now and sell later can be used as a medium of saving. They may have to make two trades to spend their savings—for example, if our saver's medium of saving is a house, they have to trade the house for balboas, then the balboas for goods. If they save directly in balboas, they only have to make one trade. And clearly trading costs, as in the case of a house, may be nontrivial. But they just factor this into their model of investment performance. There is no categorical distinction.

Four is that if any asset happens to work well as a medium of saving, it may attract a flow of savings that will distort the "natural" market valuation of that asset.

Five is that since there will always be saving, there will always be at least one asset whose price it distorts.

Levitation

A rise in an assets price will naturally draw peoples attention to it. Again, a feedback loop that is well established. Bitcoin functions like a Veblen good - as the price rises so too does the demand. In most markets this rise in demand will also spur a rise in supply. However, this is not true with Bitcoin as the difficulty adjustment ensures that the same amount of blocks (based on the particular halving cycle) are released every ten minutes regardless of the price of bitcoin on the open market.

Levitation, in other words, triggers inventory growth. Let's call the inventory growth of a levitated good "debasement." In a free oil market, debasement will counteract levitation completely. It will return the price of oil to its cost of production (including risk-adjusted capital cost, profit). In the long run, there is no reason why anyone who wants oil cannot have as much as he or she wants at production cost.

We can call the decrease in price of an asset due to the flow of savings out of it "delevitation." In our example, debasement causes delevitation, but it is not the only possible cause, savings can move between assets for any number of reasons. If savers sell their oil to buy shares of Apple stock, the effect on the oil price is exactly the same.

Won't it happen with Bitcoin?

The obvious difference is that Bitcoin is derived from bits and open sourced code that is limited in both supply and rate of supply. All humans can do is move them around for their own convenience, in other words, collect them. So, some may call bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies "collectibles."

Because it cannot be over produced, the price of a collectible is arbitrary. It is just a consequence of the prices that people who want to own it assign to it. Obviously, the collectible will end up in the hands of those who value it highest. This is readily apparent in the recent fervor surrounding the Non Fungible Token market with the sale of a Beeple piece of artwork for > $69,000,000 USD.

Mining

Since the global bitcoin inventory is 18,600,000 and ~52,500 coins are mined every year, it is easy to do a little division and calculate a current "debasement rate" of 0.02% for Bitcoin.

But this is wrong. Bitcoin mining is not debasement in the same sense as oil production, which does not deplete any fixed supply of potential oil. In fact, it only takes a mild idealization of reality to eliminate Bitcoin mining entirely.

Bitcoin is mined from a specific code, whose extent and extraction cost miners can estimate in advance. In financial terms, bitcoin "in the code" can be modeled as a call option. Ownership of X satoshis of unmined bitcoins which will cost $Y per satoshi to extract is equivalent to a right to buy X satioshis of bitcoin at $Y per satoshi.

Since this ownership right can be bought and sold, just as the ownership of bitcoin can, why bother to actually mine the bitcoins? In theory, it is just as valuable sitting where it is.

In the form of stock in Bitcoin mining companies which mine bitcoin, un-mined bitcoin competes with bitcoin for savings. Because a rising bitcoin price makes previously uneconomic mining profitable to mine, many other factors contribute to whether a miner will mine bitcoin, chief amongst them being energy costs as the mining rate does not fluctuate based on bitcoins price in the market. Think of this in terms of in the money options.

In practice, modeling unmined bitcoin as options is simple. Bitcoin mining is a complex business that is increasingly political in nature. The important point is that rises in the bitcoins price, even dramatic rises, propagate freely into the price of unmined bitcoin and cannot generate substantial surges of new bitcoin. For example, the price of bitcoin has more than doubled since 2020, but bitcoin production actually fell through the halving mechanism in 2020 and will do so again in 2024.

The result is that bitcoin can still levitate in a stable manner. Even if new savings flow into bitcoin stops entirely, debasement will be neutral. The cyclic response typical of non-collectible commodities such as sugar (or baseball cards), or theoretical collectibles whose sources are not in practice scarce (such as copper) is unlikely.

Of course, if savings flow out of bitcoin for their own reasons, it can trigger a self-reinforcing panic. Delevitation is not to be confused with debasement. Again, it is important to remember that debasement is not the only cause of delevitation.

What we have still not explained is why bitcoin, which is clearly already levitated, should spontaneously tend to levitate more, rather than either staying in the same place or de-levitating. Just because bitcoin can levitate doesn't mean it will.

The whole point of money is that its "real value" is irrelevant. In principle, an artificial money supply can be much more stable than a naturally restricted resource such as bitcoin.

In practice, unfortunately, it has not worked out that way.

Debasement

Artificial money is a political product. Its problems are political problems. It does no one any good to separate economic theory from political reality.

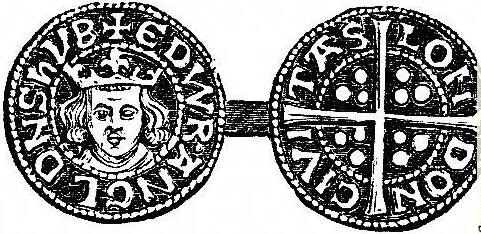

Governments have always debased their own monetary systems. Historically, every monetary system in which money creation was a state prerogative has seen debasement. Of course, no one in government is unaware that debasement causes problems, or that it does not create any real value. But it often trades off short-term solutions for long-term problems. The result is an addictive cycle that's hard to escape.

There is an English word that used to mean "debasement," whose meaning somehow changed, during a generally unpleasant period in history, to mean "increase in consumer prices," and has since come to mean "increase in consumer prices as measured, through a complex process whose opacity makes cocoa look transparent. The new word wielded to confuse people is inflation.

It should be clear that what determines the value of money, for a completely artificial collectible with no industrial utility, is the levitation rate: the ratio of savings demand to monetary inventory. Increasing the monetary inventory has a predictable effect on this calculation. Consumer price increases are a symptom; debasement is the problem.

Debasement is always objectively equivalent to taxation. There is no objective difference between confiscating 12% of existing dollar inventory and giving it to X, and printing 13% of existing dollar inventory and giving it to X. The only subjective difference is the inertial psychological attachment to today's dollar prices, and this can easily be reset by renaming and re-denominating the currency. Re-denomination is generally used to remove zeroes —for example, Turkey recently replaced each million old lira with one new lira—but there is no obstacle in principle to a 10% re-denomination. Turkey has done this more than once…

The advantage of debasement over confiscation is entirely in the public relations department. Debasement is the closest thing to the philosopher's stone of government, an invisible tax. In the 20th century, governments made impressive progress toward this old dream. It is no accident that their size and power grew so dramatically as well.

When productivity counteracts debasement, what's happening is that progress that normally would have been improving peoples' lives is being confiscated by the government. Since no one ever sees how cheap everything would have been without debasement, they tend not to complain about it so much. This is why we have cheap electronics and expensive assets. A 60 inch tv seems like a huge savings at $400, while a share of the S&P 500 at $3,900 seems overpriced.

Another approach is to use debasement for corporate welfare, by subsidizing low interest rates ("easy money") or bailing out the financial industry when risks go bad ("injecting liquidity"). If this is done properly, it can actually lower consumer prices by decreasing production costs. Prices only start to rise when increasing producer industries start to bid up the costs of the commodities and labor they need to produce. This is starting to occur in the cost of raw materials for builders - lumber, copper, and steel. Economists of the Austrian School consider this corporatist approach to finance responsible for the business cycle.

Just how much debasement is occurring? A conservative estimate of today's dollar debasement rate, as measured by the Fed's M3 number, is 10%. European numbers are similar. Chinese debasement is more like 20%. In reality, the debasement rate in the United States over the last 18 months is over 25%, think of that, if you have not made over a 25% return over the last 18 months you have lost money.

Unfortunately for the plebs, and fortunately for the government, debasement creates dependency. For example, when debasement is used to subsidize interest rates, businesses and homeowners become dependent on cheap, easily rolled-over loans. When the debasement rate is 10% and interest rates are 7%, the negative debasement-adjusted interest rate is a debt factory. It is easy for borrowers to make decisions that assume these rates will continue. If they end, the typical result is a recession. These kinds of dependencies make it very hard for politically sensitive authorities to end debasement, or even significantly reduce it.

Debasement violates the whole point of money: storage of value. As such, it gives savers an incentive to find other assets to store their savings in. In other words, debasement drives real investment. In a debasing monetary system, savers recognize that holding cash is trash so, they look for other assets to buy.

Store of Value

The consensus among Westerners today is that monetary savings instruments like savings accounts, money market funds, or CDs are lackluster. The real returns are in crypto, stocks, and real estate.

When debasement-adjusted, M3 is the reason for this. Real non-monetary assets like crypto, stocks, and real estate are the only investments that have a chance of preserving wealth. Purely monetary savings are just losing value. What else will give one +25% per annum?

When official currency is not a good store of store value, savings look for other outlets. Stocks and housing become monetized. But the free market, though it cannot create new official currency or new bitcoin, can create new cryptos, stocks and new real estate (don’t believe me? look at Saudi Arabia).

Stocks and housing do not succeed as money. Holding all savings as stocks or housing is not a Nash equilibrium strategy (though for housing in some prestigious neighborhoods it comes close, because various restrictions have given buildings in older city centers near-collectible status). Historically, holding savings in gold, and now presently in bitcoin, as we've seen, is.

Markets do not, in general, think collectively. Most investors, even professionals who control large pools of capital, have a very weak understanding of economics. As I've already mentioned, the version of economics taught in universities has been heavily influenced by political developments over the last century. The average financial journalist understands finance about the way a gecko understands quantum-physics. This has an obvious effect on retail investor psychology. It’s easy for journalists and others to grasp large narratives about the macro economy (we all love to be told stories). But, in reality things operate at the micro level and microeconomics is the harder of the two to understand, hence most are told grand stories and left in the dark about how thing actually work in practice.

Crypto, or bitcoin specifically, will only stabilize when they either defeat artificial currency completely, or are completely defeated by it—either by some new financial technology which permanently precludes debasement, or by a forcible end to the free trade of cryptos. For much of human history gold functioned in this capacity, it wasn’t until globalization really took hold that fiat money became untethered from the layer 1 of gold.

Central banks—and through them, governments—always want to minimize the levitation of any collectible that could displace their artificial currencies. Obviously this includes bitcoin. And obviously, owners of bitcoins want to maximize their levitation.

The result is a giant tug-of-war on a global, historic scale. It is no accident that until the 20th century, the nature of money was one of the most controversial political issues in the United States. It is a matter of historical fact that the pro-banking forces won in 1913, and took the question off the political table. There is no reason to assume this victory will be permanent. But there is also no reason to assume it can't be.

Bitcoin vs Gold

People have saved in gold for millennia, yet in order to save in gold, one has to pay round-trip conversion costs, including ones own time in managing the conversion. "padding" is a good name for this phenomenon, because it makes it hard for money to flow back and forth between gold and the dollar. Another form of padding is capital-gains tax, which under US law is particularly harsh on gold.

What led to paper fiat currencies? Historically banks just issued more gold-redeemable notes than they held gold. Obviously the fundamental value of a gold banknote is whatever weight of actual gold it commands. If you have one million ounces of gold and you issue two million notes, the fundamental value of each note is half an ounce, whatever you print on it. But if authorities are obliging, banks can manage the exchange rate between notes and gold, by "selling" gold for notes freely at the face value. As long as not too many people took them up on this offer, banks could create free money that traded at no discount to gold. A modern, electronic financial market would detect this error and halt it instantly, but in the days of paper ledgers it worked just fine as long as the ratio was not pushed too high.

In other words, once a bank issues more banknotes than it has gold, a banknote becomes its own artificial currency. There is no objective difference between a redemption policy and a currency peg, like the mechanism China uses to control exchange rates between the dollar and the yuan/RMB. Even in the days of the global gold standard, these fractional notes were the norm.

Central Banks

In a lease transaction, the central bank lends the gold to a Wall Street bank, which sells it into the gold market and invests the proceeds as it sees fit. This works as a "carry trade," because central bank rates for leasing gold are very low, and the Wall Street bank can earn a higher return on the cash. Of course the Wall Street bank has to pay the loan back in gold at some point, but the central bank is always happy to roll the loan over.

Another caveat, even though the central bank's gold has been sold to make jewelry or coins, and it has had the same negative impact on the gold market that any sale of gold does, central banks typically do not report how much of their gold they have leased out. In other words, they count actual gold and gold IOUs as the same thing. Interesting indeed.

In short, gold leasing lets central banks "earn a return" on a "static asset." No one could possibly believe this; you would have to be a financial alchemist. First, turning a profit is the last thing on central bankers' minds; it is not even clear what return means for an entity that can print its own money. Second, this story clashes with central banks' official motivation for keeping this static asset rather than selling it all in one giant auction, which is that gold is a money of last resort in a crisis. As, of course, it is. But leased gold will not magically reappear in a crisis.

Some analysts estimate that since the 1980s, central banks have lost more than half of their gold through leasing. Portugal released this figure, perhaps accidentally, in 2001; it had lost 70% of its gold.

The FED

Fed policy since the crash of 1987 has been to insure against risk by stabilizing crises with liquidity injections—that is, the printing of new money. It's no secret that the financial industry has responded by taking on more and more risk. Why not? Money is cheap. This vicious cycle of moral hazard is a policy that's hard to adjust. For today's Fed, short-term rates of 1% are dangerously high. 2.5% is not a serious option.

Any fractional-reserve banking and monetary system, like the United States, is destabilized by any outflow of dollars. For the Fed, what is really frightening is not a high gold price, but a rapid increase in the gold price. Momentum in gold is the logical precursor to a self-sustaining gold panic.

In a self-sustaining panic, flight to gold destabilizes the banking system and the bond market, causing waves of bankruptcy across the financial industry. The Fed's cure for bankruptcy is more liquidity—but monetary expansion only increases the incentive to buy gold. In the endgame, money flows out of the dollar as fast as the Fed can pump it in. This is the collapse scenario that leads to remonetization

Of course, the US government can play the other side of the ball and—at the very least—limit purchases of gold. But this, as we've seen, means showing fear. Wolves have nothing on hedge funds when it comes to smelling fear. Case in point with GME in 2021. It's an illusion to think that the US and its allies own the global financial system outright.

Gold

If the US imposed exchange controls on gold, the instant result would be a replacement of dollars with gold as a global reserve currency by China, Russia, and the Arab oil bloc. It is hard to imagine, for example, Dubai, closing its gold market. The result would be an international exchange rate between gold and dollars, and a black market in the US. Economists understand this very well, and I can assure you that no one wants to go there.

Remonetization of gold in 1980 had no chance at all. What the goldbugs of 1980 failed to see was that physical currency of any kind, paper or gold, was a relic. Gold could not compete with dollars because there was no way to hold or move it electronically (Bitcoin solves this problem). The only electronic market for gold was the futures market. Since most futures market trades do not exchange actual metal, but are settled for cash, futures trading in gold did not perform the critical market function of shifting physical gold from people who valued it less to those who wanted it more. Retail investors certainly did go to their coin stores and buy gold coins, but the Fed could move faster and harder.

In the end, gold is a democracy. The gold price is not set by the LBMA or the Comex. It's set by the opinions of all the people who have savings. If you could buy an ounce of gold for $1, pretty much everyone would buy all they could. If you could sell an ounce of gold for a villa in Nice, pretty much everyone would sell all they could. Somewhere in between is the current price of gold, and all that sets it is public opinion. Of course, peoples' opinions are weighted by the size of their savings, but that's the free market.

US Dollar

The dollar is a democracy, too. As former Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher stated the US dollar is a "faith-based currency." As we've seen, all money, natural or artificial, is faith-based. Gold is only different because no one can print it. The price of gold will never fall to zero because gold is good for capping teeth and electrical conductivity. The price of dollars will never fall to zero because a dollar is made from fine rag pulp with quality recyclable fibers. But everything else is faith.

Thought Experiment

From tomorrow on, the Times puts all its weight into reminding its readers of the undeniably true and objective facts that the dollar is a faith-based currency; that new dollars are being created at about 25% a year; that the current US financial system was designed a hundred years ago, in the age of Morgan, Hearst and Rockefeller, to create a steady flow of new dollars for both federal spending and corporate welfare; that the global financial system is now completely dependent on money creation, and could not survive in anything like its present form with a static money supply; that remonetization of precious metals is a Nash equilibrium; and that if remonetization happens, the first people who move their money into gold will profit the most.

Bitcoin

Over time, the Mengerian process of standardization will tend to reduce the number of monetized commodities, possibly to one. Standardization favors the leader, and it is an unstable game: since losers by definition delevitate, it makes sense to flee them as soon as possible. Since gold, just for historical reasons, is the leader, it may be the only survivor.

Recently a contender to gold has emerged with a $1T market cap (roughly 1/10th that of gold), Bitcoin is now elevated to a level of viability to replace gold as the leader, the One, the levitator. This is due to Bitcoins intrinsic value which is derived from its immutability, scarcity, and mobility.

According to Menger's model, money standardizes because it is inconvenient to be constantly converting value between multiple moneys. But it's a lot easier with computers. And one effect that tends to counteract Mengerian standardization is the obvious desire to diversify one's savings. Bitcoin fills a void for those looking to save wealth in a currency that is outside of direct governmental control and appreciating in value against the US dollar and gold.

A Bitcoin ETF

The recent talks around the opening of a Bitcoin ETF, makes such an increase likely; in fact, bitcoins price has surged while the ETF is going through the approval process. Once approved the ETF will function like a sink hole for bitcoins, sucking down thousands a day, which is clearly unsustainable due to bitcoins cap of 21,000,000.

So there are three factors favoring the monetization of Bitcoin. One is the increasing relationship between Bitcoin and the traditional markets. Two is the fact that since central banks hold zero to very little bitcoins, it's hard for them to manage the price. Three is that since no one really has much bitcoin at all, any flow back into the ETF will cause some serious levitation.

One Nash equilibrium strategy for Bitcoin is to quantitatively value the mineable. This seems to be the strategy that people followed before the age of artificial currencies.

The new US currency should be satoshis. Stock markets should be repriced in satoshis according to the dollar exchange rate, and reopened as soon as possible.

Property rights of existing bitcoin holders should be respected. However, some bitcoin confiscation is inevitable. Since the concept of capital gains on bitcoin becomes meaningless with a bitcoin currency, all holders of bitcoin who are US citizens should pay an immediate 15% tax on their entire holding, in lieu of the existing rate on capital gains tax. 15% is large enough to be significant and small enough that it won't stimulate excessive evasion. Similarly, mining rights should be preserved, but a similar royalty should be applied.

The characteristic quality of money is a high stock to flow ratio: much more is stored than is created every year. As of 2021, Bitcoin has a higher stock to flow ration than gold. In the near future it will have the highest stock to flow ration in history.

Cryptocurrencies are competing with precious metals, fiat currencies and risk assets (real estate, bonds)—the last of which still stores by far the majority of savings.

Bitcoin is is mainly used as a store of value. Its price is the market cap of all the bitcoin in the world, divided by the amount of bitcoin in the world. Obviously, in an economy on a full bitcoin standard, if more bitcoin is mined then used up each year, it makes no sense to say that the price of bitcoin is too high.

As a store of value, price depends wholly on the level of monetization. For bitcoin this number is small, but quickly rising. The Achilles heel of maturity transformation is that once a lot of people start selling, its price has an unnerving tendency to decline.

The notion of “worth” is not an absolute Platonic quality of an object. An object’s true worth, its intrinsic value, may even be spiritual and unchanging. The same is true of an asset. However, its market price is only what someone is ready to pay for it.

The price of a promise is the amount of the promise—times the probability that the promise will be redeemed—times the discount rate for the term of the promise. The discount rate is just the inverse of the interest rate. If the interest rate is 2% a year, a promise of 100 dollars a year from now is worth about $98 now—that’s the discount.

Use cases

Gold can be turned into jewelry or used in medical devices; real estate can be used as accommodation, and US dollars are a globally accepted means of payment. The fact that these assets have an allegedly reliable real-world use case gives them their function as a store of value. Asset owners can save, retrieve and exchange them at a later time.

However, much of traditional assets’ utility is more perceived utility than actual real-world utility. According to the World Gold Council, industries use only 15 percent of all gold available. The majority goes toward making jewelry, gold bars, and coins — gold has value mainly because people perceive it as valuable, not because of its real-world use case.

Unlike a traditional commodity that can be turned into something that provides utility, Bitcoin’s intrinsic value is in the way how mathematics is used to provide a trusted network. Bitcoin does this in a unique way, that no other commodity has done before. Saying Bitcoin does not have any intrinsic value because it is not a raw material would be like saying a human brain has no value because it consists mostly of carbon and water.

Bitcoin is a new type of commodity, a “service commodity,” that gives direct access to a service, not a raw material. It offers access to an automated ledger service that was previously only available as a service offered by banks. And banks are highly profitable, so there must be some value in the service they provide.

Fiat

What the banking system did, by transforming demand for present fiat into demand for future fiat, was to create a false economic signal of spurious demand for future fiat.

This false signal increased the price of future promises, creating a false signal of low interest rates, and naturally increasing the production of promises. When the illusion collapses, there are more promises than anyone wants. So the real interest-rate signal, now exposed because the tide has gone out, is unusually—but not unfairly—high.

This classic bank run is actually the popping of a bubble—a bubble in promises. It is a transition from an unstable equilibrium to a stable equilibrium. A good rule of thumb is that if Reddit can blow it up, it’s probably not stable.

The price of bitcoin cannot be set by production and destruction like a commodity. It is set by dividing a pool of savings over a pool of coins. Unlike, if I print out a fake coupon for fiat, and sell it, I have created what Ludwig von Mises called a “money substitute.” It is not counterfeiting per se, because the coupon has my email address on it—I have created a corresponding liability.

The systemic effect of this synthetic fiat is to distort the market for fiat, in a way that the market for bitcoin cannot be distorted. Perhaps the demand I create for fiat in my attempts to repay the liability counters this dilutive effect—perhaps it doesn’t.

Bitcoin banking

Generally, fractional-reserve banking can create as many claims to present assets as people are willing to create promises of future assets. This is why people say banks “create” money. A Bitcoin bank is not a supernova and cannot create bitcoins, but it can create synthetic present bitcoin out of promises of future bitcoin.

So, besides mining, there seems to be some other source of promises of future satoshis. To describe this as “borrowing” bitcoin is misleading—who actually “borrows” bitcoin? Unlike an Aston Martin, it is useful for exactly nothing—unless you use it. Some use borrowed bitcoin to stake in contracts, others to speculate on exchanges.

All we know is that, while the bitcoin banks proper keep balanced books, someone is selling them promises of future bitcoin; and said sellers have good enough credit to convince the banks that their promises are good, letting them resell these promises by issuing claims to current bitcoins. We see this language now being used by companies acccepting bitcoin for their products - see Teslas fine print on swapping your bitcoin for one of their cars.

This is not a conspiracy. It is just banking. Why should the bankers care how their counterparties are going to get this bitcoin, so long as their credit is good? The promises are not even promises of bitcoin, anyway—just promises to pay whatever bitcoin is worth. The bank does not care who is making these promises or why. It gets the promises in its inbox, and turns them into synthetic bitcoin in its outbox.

So besides the risk of a classic bank run with its interest-rate spike and drop in the price of future bitcoins, there is also the risk of a pattern of systematic failure in the promises of bitcoin that the bank holds.

If these promises are ultimately backed by actual bitcoin, bitcoins-price increases should not endanger their reputation. If they are the result of pure financial alchemy, who knows? Margin is a good thing, but it is not a perfect solution to the problem of counterparty risk. Done at sufficient volume, shorting a monetary commodity actually creates its own profit. It is necessary to carry this short, taking on risk, and to find a way to cover it.

Conclusion

Hard money has reigned for the majority of advanced civilizations. It has been but recently that we have seen the rise of fiat currencies being the dominant form of money. The reemergence of hard money in the form of Bitcoin signifies the rise of the most credible monetary policy in history circumventing the most untrustworthy monetary policies in history. A bet on Bitcoin is that the competitive dynamics inherent to the market for money will continue to play out in the same way they have throughout all of history.

Moreover, the monetization of the bitcoins is a feedback loop—they go up as savings move into them; savings move into them as savers see them going up. This loop can continue indefinitely—any cryptocurrency can store all the world’s savings.

Both gold and Bitcoin are hedges against the fiat system that is rapidly printing money and debasing the currency. Gold was the soundest money on a relative basis for thousands of years. However, gold is the analog version of sound money while Bitcoin is the digital version. In time, everything is moving to nits, including the primary store of value. This is why, in the long run, most of the wealth that is stored in gold will find its way over to Bitcoin. It is the best safe haven asset and best store of value that currently exists.