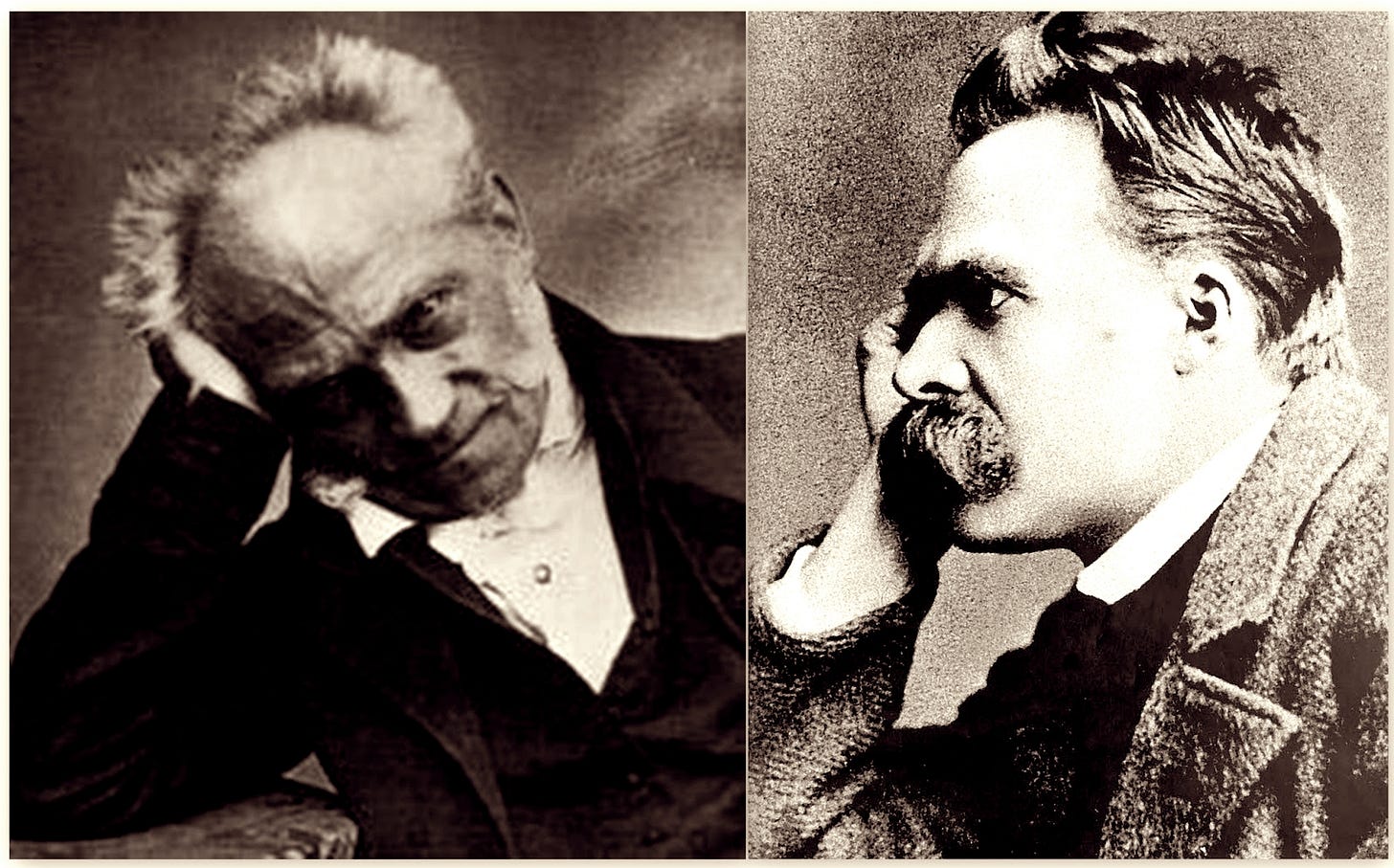

On Psychology Without Freud

Schopenhauer and Nietzsche Against Consolation

“Life is suffering.” — Schopenhauer

“Become who you are.” — Nietzsche

Between these two sentences lies the only psychology worth speaking of. One strips existence bare; the other commands its transfiguration. Together they give us the grammar of man: suffering and creation, abyss and ascent.

The history of psychology is often written as if it began in the …