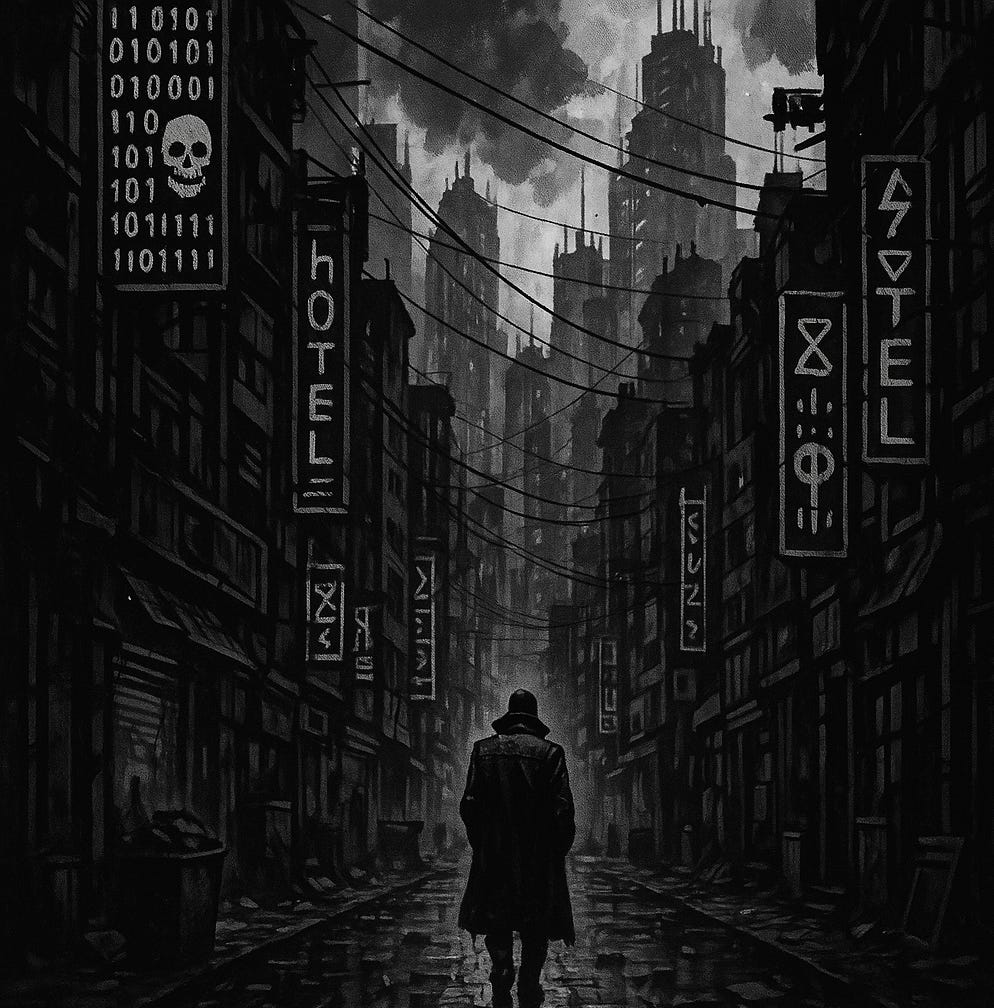

On Princes to Programmers

How Japan’s Monetary Past Foreshadows America’s CBDC Future

“Give me control of a nation’s money supply, and I care not who makes its laws. - Attributed to Mayer Amschel Rothschild

In the shadows of parliaments and presidencies, beyond ballots and campaign slogans, lies a quieter but deeper power: the power to create credit. This is not the power to tax or spend, it is the power to conjure capital itself, to dete…