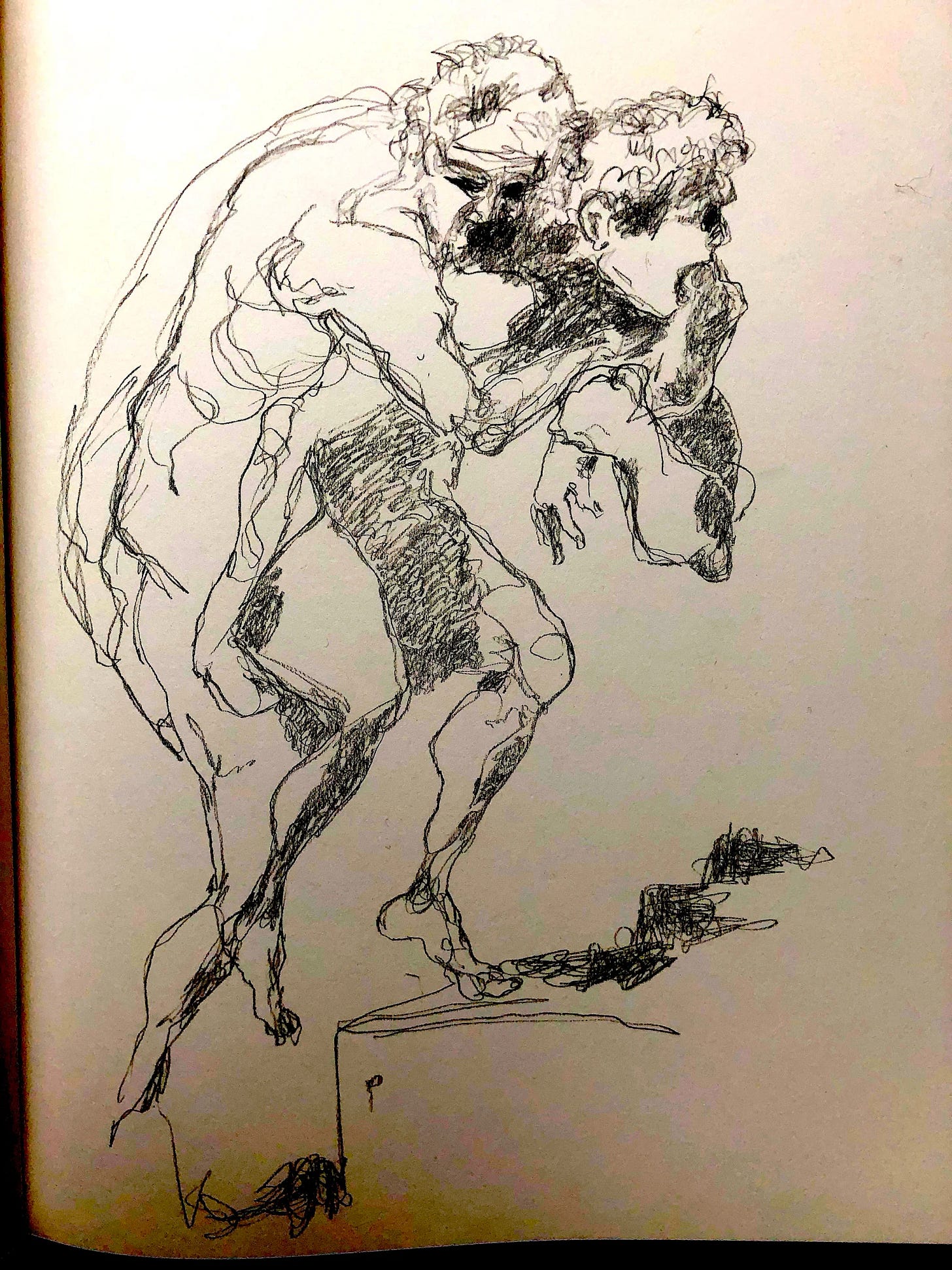

On Experience

Ut est rerum omnium magister usus (experience is the best teacher)

The art of storytelling is reaching its end because the epic side of truth, wisdom, is dying out. - Walter Benjamin

What is experience? It is the feeling in response to a challenge, is it not? To respond to a challenge is experience. And does one learn to experience? When one responde to a challenge, to a stimulus, ones response is based on ones conditio…