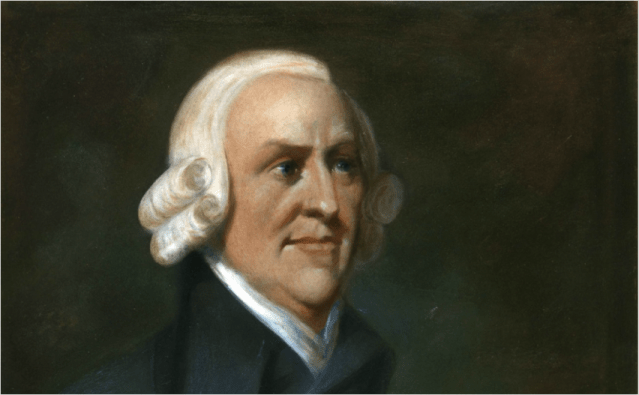

On Adam Smith

Reuniting Adam Smith’s Moral Philosophy and Political Economy

“The great source of both the misery and disorders of human life seems to arise from overrating the difference between one permanent situation and another. - Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

I am once again asking people to read both The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Smith’s invisible hand makes no sense without his mora…