Foundational Habits Pt. 2

On Nutrition

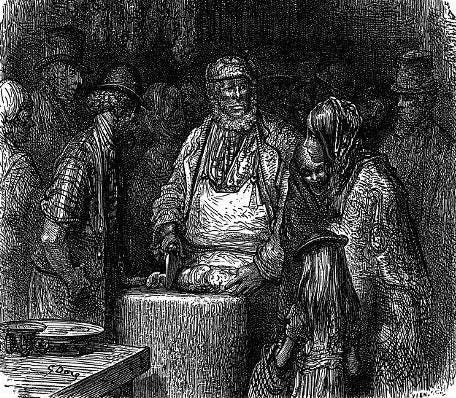

The ancient Cynic and Stoic philosophers were very interested in food.

“And indeed, at each meal there is not one hazard for going wrong, but many. First of all, the man who eats more than he ought to do wrong, and also the man who wallows in the pickles and sauces, and the man who prefers the sweeter foods to the more healthful ones, and the man who do…